Death Valley Days End

In the desert, life-threatening stresses aren’t a crisis; they are a normal feature of the life cycle.

Hope Jahren, Lab Girl

The National Park Service (NPS) supplied map and Death Valley National Park Visitor Guide both say “Welcome to Death Valley!” in large friendly letters. Then they immediately proceed to try and scare you shitless. The Visitor Guide has a page entitled, “Get Out and Hike!” and immediately underneath it warns: check weather conditions; watch out for flash floods; carry water; don’t hike in low elevations when its hot; footing can be rough and rocky; and be aware of illegal marijuana grow sites. The park map includes all these (except the marijuana one), with the addition of keep out of mines and do not rely on your cell phone. However, this article noted that between 2010 and 2020, Death Valley was only number 7 out of 62 National Parks on the Deaths per Million Visitors list, and that the majority of deaths in the park were due to motor vehicle accidents. I would add, “Practice defensive driving and Watch out for idiotic drivers” to the warnings. We saw a lot of idiotic drivers.

Mesquite Flat Sand Dunes

Number 4 on the National Park Service Must-See Locations list, Mesquite Flat Sand Dunes is quite spectacular and difficult to miss as it is on the main route through the park. Located near the way station of Stovepipe Wells Village (or vice versa, actually), the dunes are visible for miles. We attempted to get there a couple of times at least near the photography “golden hour,” to get the shadows in the dunes in really sharp relief, and we got close. Luckily it was February, so the sun didn’t get very high in general.

Taken from the Ranger Station at Stovepipe Wells way station with my 70-300 telephoto lens. The Funeral Mountains are the backdrop (ISO 640, 205mm, f/16, 1/240s)

Taken from Hwy 190 with my telephoto lens. The Grapevine Mountains are in the background and Kit Fox Hills in the mid-ground (ISO 100, 70mm, f/4.5, 1/640s)

Taken from Scotty’s Castle Road rest area with my telephoto lens. Stovepipe Wells way station and campground are visible behind the dunes, and the base of the Panamint Range is in the upper part of the photo. (ISO 2000, 300mm, f/22, 1/320s)

Taken from Hwy 190. Grapevine Mountains and Kit Fox Hills in the background. (ISO 100, 70mm, f/4.5, 1/800s)

Taken from Hwy 190 with Grapevine Mountains and Kit Fox Hills in the background. (ISO 400, 97mm, f/22, 1/100s)

Close-up - Kit Fox Hills in the background (ISO 1250, 177mm, f/22, 1/200s)

We decided to try and find the Historic Stovepipe Wells site (California State Historical Landmark #826) that is on the edge of the dunes, about 5 miles as the crow flies from the current Stovepipe Wells. Historically, it was the only water to be found in the dunes area - apparently originally two shallow pits (the only reference I could find as to why the name might be plural) - at the crossroads of two Native American trails.

Rhyolite, Nevada and Skidoo, California, now ghost towns, were boomtowns during a short gold rush in the early 1900s. These “wells” became an important water source for gold miners traversing Death Valley between the two towns when the Rhyolite to Skidoo cross-valley road was created. Apparently to access the water, the person had to dig a hole in the sand and wait while fresh water seeped in. Sand, however, kept covering the watering holes, as sand dunes are wont to do, so eventually two miners decided to mark the area for other miners with a stovepipe. That stovepipe is long gone, but the name stuck, and someone at some point has set another one in concrete, possibly over a more permanent well at or close to the original site(s).

When we arrived, we also noticed a lot of tracks in the sand in the area: roadrunner, kangaroo rat, and what we think were scorpion tracks.

The current stovepipe over what looks like a capped well. Made in Kendallville, Indiana. The dunes and Panamint Range in the background (ISO 320, 72mm, f/22, 1/80s Polarizing filter )

Bob noticed a trail coming down the alluvial fan from Kit Fox Hills and ending right at the well. You can see the faint trail if you look closely. Maybe one of the Native American trails? (ISO 800, 70mm, f/22, 1/80s)

Road runner tracks. Beep Beep! (ISO 500, 75mm, f/22, 1/80s)

More road runner tracks (ISO 500, 76mm, f/22, 1/80s)

Kangaroo rat tracks over human tracks. You can see that he hopped, and his tail dragged through the sand (ISO 500, 70mm, f/22, 1/80s)

Either a small rodent or a lizard, but you can see the tail was dragged through the sand (ISO 800, 100mm, f/22, 1/125s)

Bob noticed these really weird tracks. I think it was a scorpion. Kangaroo rat tracks for comparison (ISO 2500, 244mm, f/25, 1/250s)

Harmony Borax Works

Number 6 on the Must-See list is the Harmony Borax Works (I told you I would eventually get around to borax!). This was where the famous Twenty-Mule Teams would set off towing two giant wagons full of nine metric tons (10 U.S. tons) of borax ore on a 165 mile journey to the nearest railway spur in Mojave, California. The teams were actually made up of 18 mules and two large horses. The horses were big enough to get the wagons moving and deal with the movements of the hefty wagon tongue. Two teamsters accompanied them, one of whom generally rode one of the horses. Behind the wagons the mules towed a large tank full of 4,500 liters (1,200 U.S. Gallons) of water for themselves, while water for the men was carried in barrels on the sides of the wagons. The tank and barrels were refilled at various springs along the way.

The 180 foot long (including the mules) wagon train could make about 17 miles a day on average, so permanent encampments were set up at about this interval along the route. Rather than hauling empty wagons back from Mojave, the teams hauled feed for two trips - their current one as well as enough to leave at each of these encampments for the borax-loaded team coming the opposite direction.

Harmony Borax Works went out of business in 1888 and eventually was bought by the Pacific Coast Borax Company (I previously mentioned them in this post). The 20-mule teams only hauled borax out of Death Valley between 1883 and 1889, but they have lived on as a symbol of borax ever since - mainly due to a very good marketing campaign by the Pacific Coast Borax Company.

Titus Canyon

Titus Canyon runs in an east-west direction through the Grapevine Mountains in the Amargosa Range in the Northeast section of the park. We saw it on a map and decided to drive out down the gravel road as far as we could go. We were about a quarter of a mile down the road when ROARRRRR!!! THWACK THWACK ROARRRR!!! THWACK THWACK THWACK ROARRRRR!!! three large dirt bikes went flying past us skidding around and pelting the van all down side with gravel. It scared the living daylights out of us, but before we could start really swearing or even take a breath, ROarrrr!! ROarrrr!!, ROarrrr!!. Another three large dirt bikes flew past - at a slightly more sedate pace. They were skidding around, but didn’t throw gravel up.

We had recently had the windshield replaced - which was NOT cheap, and some of those rocks hit pretty hard and sounded as though they might have done some damage. Then Roar! Roar! Roar! Roar! Another three or four - riding much more carefully. Bob was furious. I was the kind of angry you get after you’ve been suddenly frightened. We leapt out of the car and Bob flagged down the last two riders - who were riding BMW adventure bikes very carefully - and pretty much told them that if the windshield was broken, he was going to drive up and find those first riders. We hadn’t had time to inspect the car, so we didn’t know if anything was dented or broken. The two men apologized and said they would go and have a word with the first riders. They very carefully rode past the van.

We examined the van, and surprisingly did not find any damage to the glass despite all the noise (we actually have since found chips in the paint after washing the van, some of which may have come from this incident). We had completely lost interest in seeing Titus Canyon as the whole debacle had left a bad taste in our mouths, and we were still too angry to be civil to the motorcyclists up ahead so we found a wide spot in the gravel road and did a 5 point turn and left. We drove to the Furnace Creek Visitor Center and reported them to the park rangers.

Charcoal Kilns

The last place we were going to check out prior to leaving the park was the Wildrose Charcoal Kilns site in Wildrose Canyon on the west side of the Panamint Range between Rogers Peak and Wildrose Peak. We had driven up a long, winding road over to the west side of the Panamint Range and were about three miles from the kilns when we saw a rather large group of motorcycles and motorcyclists parked along the road up ahead.

Bob said, “I wonder if those are the same group?” It was about five hours later, and we were almost 60 miles by road, 37 miles as the crow flies, and about 5800 feet in elevation away from where the “incident” had happened.

“They can’t be” I said hopefully. My hopes were dashed when several of the cyclists started waving their arms and flagged us down. Bob stopped the van and rolled the window down with slight trepidation. They had us way outnumbered.

One of the guys yelled “Are you the van we met earlier?”

“Yes.”

“We want to REALLY apologize for what happened. Is your window broken?” A couple of them started trying to inspect the windshield.

We had to assure them several times that there was no harm done, and they guy who had thrown up most of the rocks kept apologizing over and over and offering us money if there was any damage and saying he didn’t know what got into him. He had apparently waited at the parking area at Titus Canyon for us with a big wad of cash and was disappointed when we didn't show up. We didn’t tell him that he probably didn’t have nearly enough on him to pay for this particular windshield. We had assumed that the first guys through were a bunch of irresponsible teenagers, but this guy was obviously in his late twenties if not his early thirties.

We finally managed to extricate ourselves and continue driving to the charcoal kilns; I believe we AND the motorcyclists felt better after this encounter. We didn’t tell them that we had reported them to the park rangers…

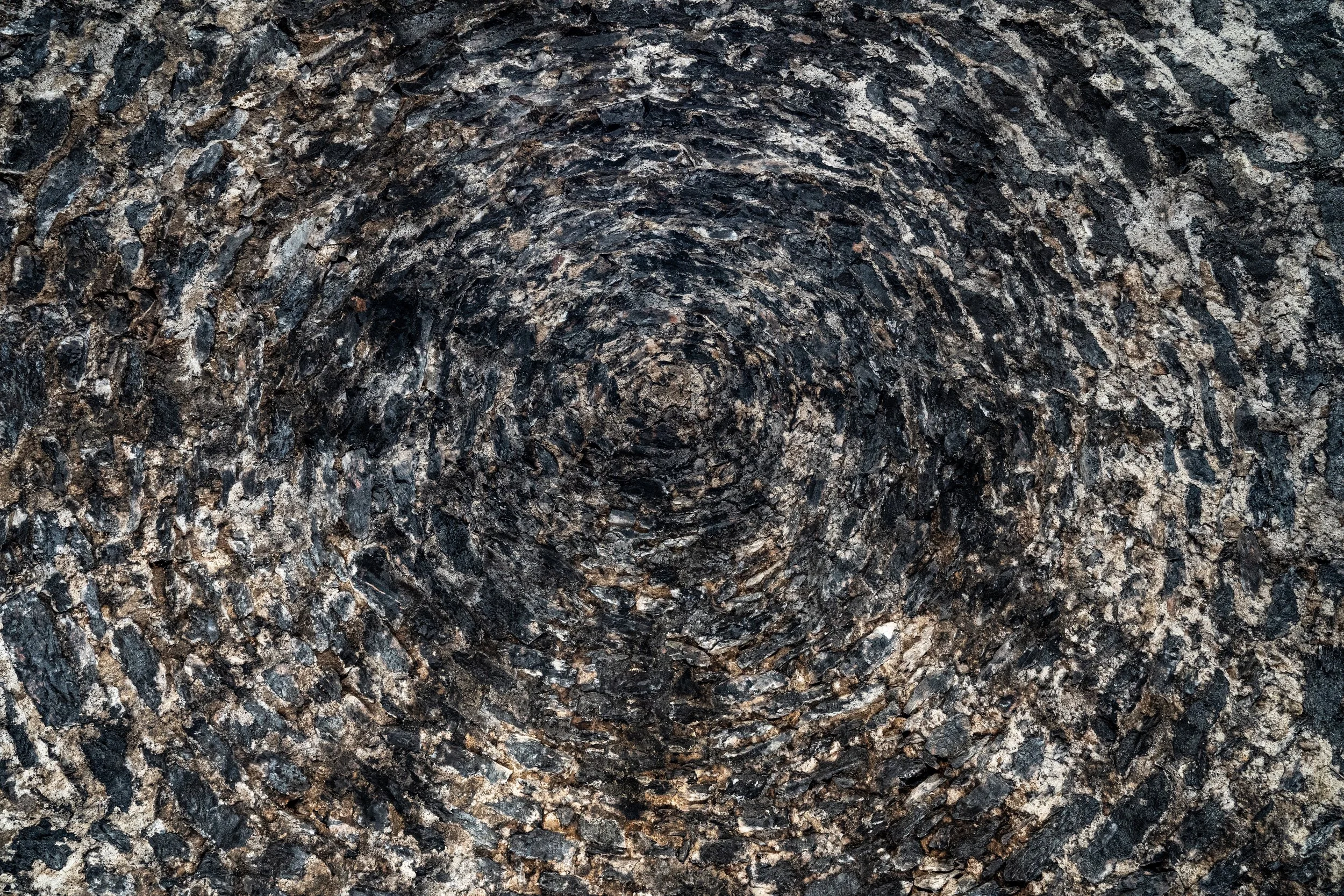

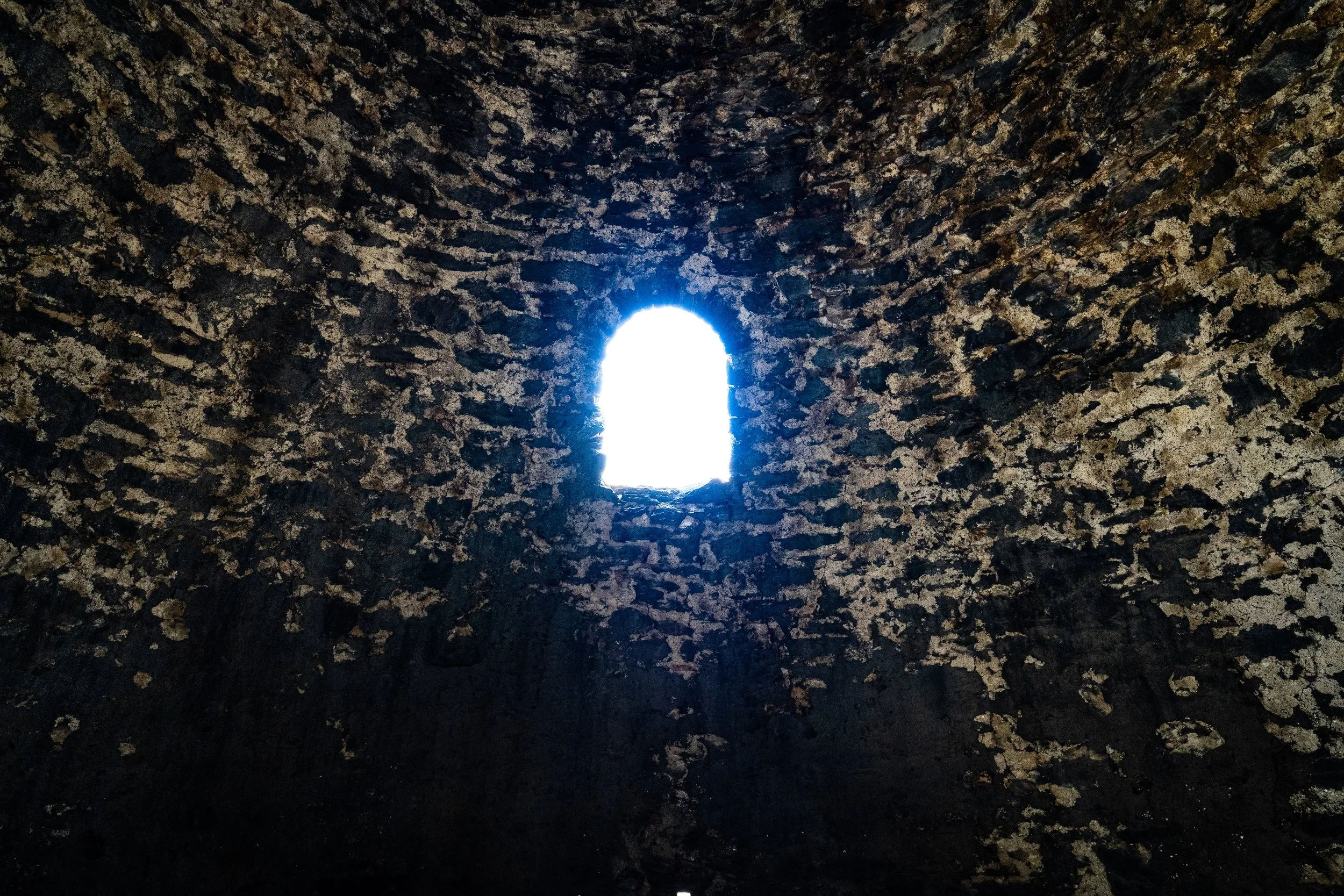

These kilns are Number 8 on the Park Service Must-See Locations list. According to the Park visitor guide, “These ten beehive-shaped structures are among the best preserved in the west.” The NPS website states that they were built in 1877 by the Modock Consolidated Mining Company to provide fuel for two silver smelters in the nearby Argus Range west of Panamint Valley and likely were only used until 1879. Charcoal was used by the smelters because it burns much hotter than wood. The westernmininghistory.com site explains that each kiln would be loaded with up to 35 cords of piñon pine, the wood was lit, then the airflow was restricted to slow the burn rate. The wood was allowed to burn slowly for a week, until it was reduced to charcoal. It took another five days for the charcoal to cool enough to be transported the 25 miles to the smelters.

One of the interesting things with these particular kilns was that one of the owners of the Modock Consolidated Mining Company was George Hearst, played brilliantly by Gerald McRaney in the HBO series Deadwood… George Hearst also happened to be the father of William Randolph Hearst.