Owens Valley

Whiskey is for drinking; water is for fighting over.

Usually attributed to, but probably not Mark Twain

Many many years ago - after I finally graduated with my Bachelors degree - I got my first job as a professional scientist with an environmental consulting firm. My first day on the job I signed paperwork, hopped in a car with four strangers, and left for three weeks to go out in the field as part of a crew doing Instream Flow Incremental Methodology (IFIM) studies in the Owens River Gorge. Which didn’t have water at the time. So we were doing dry IFIM. It took a bit of imagination.

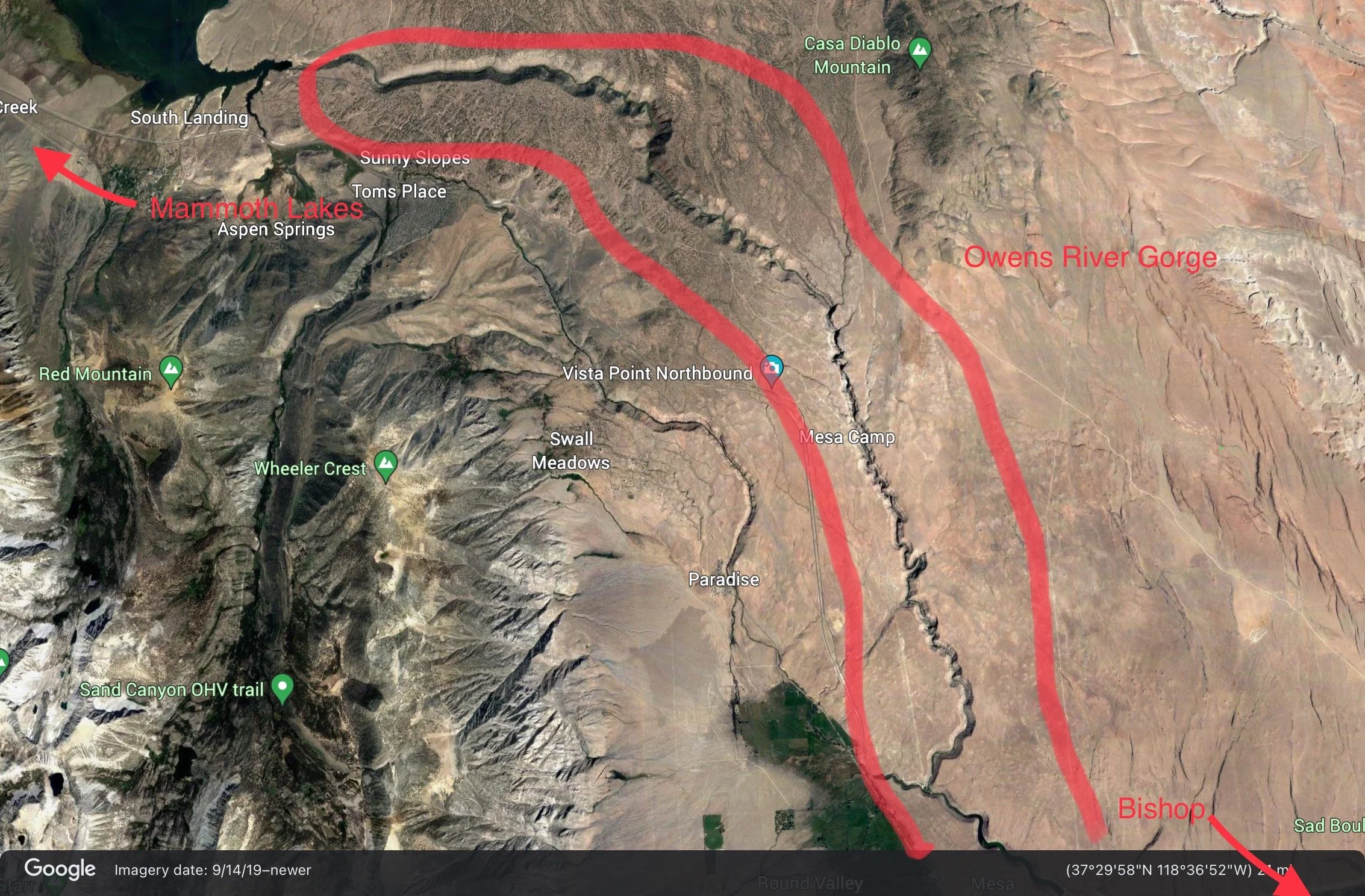

The Owens Gorge is a ten mile long canyon on the Owens River that roughly parallels Hwy 395 between Crowley Lake and about 12 miles north of Bishop. We stayed in the town of Mammoth Lakes rather than Bishop because our crew leaders were of the opinion that the restaurant choices in Mammoth Lakes were better. For more information on the reason the Owens Gorge was bone dry look up the California Water Wars. I also highly recommend reading Cadillac Desert by Marc Reisner about this history of water in western United States. It is fascinating. We were doing studies for the Los Angeles Department of Water and Power (LADWP) because they were legally obligated to release water into the gorge and were trying to determine the absolute minimum amount of water they needed to release to protect fish. This article explains why they were legally obligated. It describes a broken pipe (penstock) that was the main reason they had to release water for the first time in 50 years. I flew over this penstock in a helicopter while I was there and “broken” was an understatement. This eight foot diameter pipe looked as though it had been pried apart using a giant can opener. The old fashioned kind.

Back to the present. As I noted in my previous post, Bob and I stayed in Bishop for several days, and I explored the area much more in-depth than I had previously. The Owens Valley lies between the Sierra Nevada Mountain Range to the east and the White and Inyo mountain ranges to the west. While Death Valley just to the southeast is the lowest valley elevation-wise in the United States, the Owens Valley is the deepest because the mountains on each side are so high. It sits in the rain shadow of the Sierras, so it gets very little rain. While it is naturally arid, it does get a lot of water from snow melt, but it is made artificially much more arid as most of the water gets siphoned off to Los Angeles. This valley supplies a large percentage of L.A.’s water.

I drove out to the Owens Valley Northbound and Southbound Vista Points. The views from these vista points are spectacular on a clear day.

Mount Tom from the Southbound Vista Point

The glacially carved spines are evident from this angle

Sigma 24mm F1.4 DG DN lens (ISO 100 f/16 1/200s) Cropped in iPad Photos

This photo shows the valley down to the Bishop area (brown area). If you look closely, you can see a dark stripe down the middle. That is the Owens Gorge.

Sigma lens (IS0 100 24mm f/16 1/160s)

The view from the Northbound View Point was almost as spectacular. From this one you can see the Sierras, but there is also a pretty good view of the White Mountains.

The White Mountains from the Northbound 395 View Point

Sigma 24mm lens (ISO 100 f/16 1/80s)

The following photo was (pretty obviously) two photos stitched together to try and create a panorama. I think I need a better program. Also, I don’t think the sky was actually quite that blue.

The White Mountains

Tamron 70-300 f/4.5-6.3 lens

(ISO 100 171mm f/22 1/40s)

Past: The work in the gorge involved a lot of hiking and carrying our gear down steep cliffs and along the dry riverbed to get to our transect sites. Often we could at least drive down to one of LADWPs three gorge powerhouses to get a bit closer. One of our sites was in the big horseshoe bend that can be seen on the Google Earth photo above. There was really no way to hike in and out easily in one day, so DWP suggested we use one of their helicopters. We met the helicopter at the Control Gorge Powerhouse. It was a Bell 206L Longranger which is a fairly large seven seat (including the pilot), two bladed helicopter that they used to fly their power lines and transport DWP bigwigs. We talked to the pilot, who gave us a safety briefing and we found out that he was a Vietnam Vet who had literally thousands of hours flying helicopters.

We loaded our filthy-by-this-time gear into the compartment near the tail rotor and climbed into the spotless interior in our dusty boots. Everyone agreed I should sit up front next to the pilot since it was my first time in a helicopter (that I remembered, anyway - apparently I was in one when I was about two). The pilot lifted off.

It was one of the most exciting experiences of my life. He flew through the winding canyon just below the rim while we all had the time of our lives. It was WAY more fun than any Disney ride I’ve ever been on before or since (sorry Jennette). He landed at a wide spot in the horseshoe bend, creating a huge cloud of dust. We jumped out, and unloaded our gear. Then we all took cover as he created another huge cloud of dust as he took off. Jamie, the other woman on the crew, and I ran behind a large rock and into a shallow cave where we watched as the helicopter rose into the air.

We were still giddy from the ride and talking excitedly about how amazing it was. As the thumping sound of the helicopter faded, another sound caught our attention. A loud buzzing. We looked around, and there was one of the largest rattlesnakes I’ve ever seen stalking past us out of the cave in a huff (if snakes can stalk. It was certainly doing its best) since we were obviously just ignoring it. It was more than a little peeved. Jamie and I just looked wide-eyed at each other.

That pilot was amazing, by the way. Later on in the trip, we were working in the riverbed near one of the upper powerhouses, and he flew in to pick someone up. There wasn’t enough room to land the helicopter, so he perched with the front of the skids on the dirt road, the back of the skids and the tail rotor out over the cliff and the blades spinning a foot or two from the cliff wall.

Back to the present: while I was driving around, I took some photos of the clouds and the white mountains. Bob looked at the photos and said, “You got a photo of the gorge!” I had not even noticed that I could see the gorge while I was taking the photos. I was concentrating on the foreground and the mountains in the background and didn’t recognize the middle of the scene for what it was.

The accidental view of the Owens Gorge with the penstock down to the Control Gorge Powerhouse

Tamron lens (118 mm ISO 800 f/22 1/125s)

Mount Tom and Wheeler Ridge from the road that runs along next to the penstock. There was a storm coming in.

Sigma 24mm lens (ISO 100 f/16 1/50s)

Owens Valley is a graben valley which means it is a block of land between two faults. It drops as the mountains rise. In the photo below you can see the transition from valley to mountain is quite abrupt (made even more evident by the snow-line).

Mount Tom. You can see how the Sierras just rise straight up from the valley.

Tamron 70-300mm lens (ISO 100 70mm f/5 1/800s)

The summit of Mount Tom. The sky was very blue, but I think my polarizing filter enhanced this.

Tamron 70-300mm lens (264mm ISO 100 f/6.3 1/500s)